PRINT

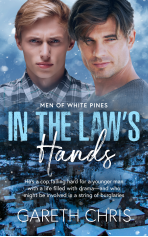

Two single dads. One unexpected love that shatters every certainty.

Upon learning his late uncle bequeathed him his White Pines, Vermont home, gay New York novelist Myles Parker decides to move there with son, Joshua. When they arrive, Myles learns the home has fallen into disrepair. Adding to his concerns, the neighbor next door is as unwelcoming as he is handsome.

Since construction worker Adam Tilson’s wife left him and their son, Flynt, a dozen years earlier, he’s shunned relationships that exceed an evening. He isn’t keen on making friends with the sophisticated city guy who moved next door. But when his son and his neighbor’s click, Adam’s resistance lowers, especially once Myles offers him a lucrative house renovation project.

Guilted by Flynt, Adam hosts his neighbors until the Parkers’ home can be habited. Although Adam believes the proximity will be an annoyance, he and Myles bond as single fathers and friends. When their boys begin to behave like the four are a family, Myles worries his growing feelings for Adam will be unrequited, and Adam grapples with his attraction to a man.

General Release Date: 27th January 2026

“This is it?” Joshua asked from the backseat—my thirteen-year-old son’s disappointment was apparent.

I drove the SUV to the end of the driveway, taking a closer look at the White Pines, Vermont home that my late uncle, Ned, had willed to me. I hadn’t remembered it looking so weathered from recent photos that my uncle had shared when he’d visited me and Joshua in New York City.

“The attorney warned me that it needed some renovation,” I reminded my son. I hoped it didn’t need a wrecking ball.

“Are you sure this is the house you used to come to as a kid?” Joshua said, staring at the structure like it was a notorious murder scene. “I thought you said you had nice memories.”

I did. My uncle and aunt had been good to me. They had been considered the ‘poor’ side of the family, disdained by my mother and father. Although my parents had referred to them as a white-trash couple, they’d been happy to send me and my sister Michaela to Vermont on summer vacations. Mother’s and Father’s dislike of Uncle Ned and Aunt Grace didn’t outweigh their desire to be child-free during boarding-school breaks.

I sighed before putting the car in park and cutting the engine. “Let’s check it out.”

If my new house was in disrepair, it didn’t compare to the eyesore in the driveway that abutted my property—a beat-up pickup truck that had as much rust as the sunken Titanic. While the owner’s smaller house was in far better shape than mine, the yard was cluttered—a basketball hoop at the end of the driveway, a trampoline, jungle gym, soccer net, fire pit, gas grill and plastic Adirondack chairs. The only things missing were the plastic flamingos and bird bath.

Joshua glanced in the same direction, wariness on his face. “They must have kids, Dad. There’s lots of…sports stuff.”

I nodded. Joshua didn’t have an easy time making friends. He was shy, studious and serious. Unlike most boys his age, he wasn’t into sports or outdoor activities. His happiest moments were times spent with his books, crossword puzzles and computer games. I wasn’t certain I wanted the influence of the neighbor kids on him anyway.

“Listen, people aren’t required to be friends just because they live next to each other. Don’t worry about them.” I put a hand on his shoulder and led him to the front door.

The latch turned with the key, but the door stuck. I shoved my weight into it to swing it open. My momentum, followed by the sudden lack of resistance, nearly sent me to the floor of the foyer. I shot Joshua a small smile, hoping he’d find humor in it. He didn’t.

“Maybe you should sell it so we can stay in New York City,” Joshua suggested. He cast his eyes down when I frowned.

“Give it a chance, Joshua.”

I did a cursory study of the ceiling, floor and walls in the front hallway. There wasn’t much in the way of damage, but the hardwood and trim needed refinishing, and the outdated wallpaper had to go. The light fixture was something from the nineteen-seventies that I’d want to replace.

“Look, Dad,” Joshua said, having entered the living room before I could. I passed through the archway to see what had grabbed his attention. “There’s a rifle over the fireplace.”

I hadn’t recalled my uncle ever being a gun owner, but perhaps everyone in White Pines was. I imagined there were bears in the woods behind the house that needed dissuading from backyard visits. My uncle was too kind to kill, but he might have sent off warning shots. It was still more than I was willing to do. “That will be one of the first things I get rid of.”

“Do you think it’s loaded?” Joshua wondered, approaching the weapon.

“Don’t touch it,” I commanded, more harshly than I had intended. “I don’t know if it is, so it’s better to be safe than sorry,” I added in a softer tone.

The living area opened to a smaller room that could be used as an office. I was pleased that it received an abundance of light because of its many windows. I was less happy that the windows overlooked the house and offensive yard next door.

We returned to the living room and made our way to a family room behind it. It hadn’t been updated since I had seen it years earlier, but it was a large space which connected to a U-shaped kitchen. To my surprise, the cabinets and appliances were newer and passable for the time being. There was a tiny windowless half-bath tucked beside it. We made our way through an old-style pantry, which had an archway to the front-facing dining room. Upon entering that area, I pointed out to Joshua that it had yet another large opening to the foyer, opposite the living room we’d first investigated.

“All the first-floor rooms are built around the staircase in the hall,” Joshua noted.

“Yes,” I said. “Come on, let’s see the bedrooms.”

The floorboards of the stairs creaked with every step we took. I had no idea if that was normal for an old house like this one or if there were bigger structural problems. At the top of the landing, there were four doors—two to the left that opened to decent-sized bedrooms, one straight ahead to a bathroom that looked original to the nineteen-twenties house, and another to the right that led to a front-to-back primary suite. That room included a tiny, newer windowless bathroom. Uncle Ned once shared with me it had been a walk-in closet that had been converted for convenience.

“Everything’s so old,” Joshua observed.

Our smaller city apartment was far more appealing than this place. To my son, this had to be worse than anything he might have imagined.

“We can change everything,” I assured him.

He peered at me with an apologetic smirk. “Even our minds about living here?”

I grabbed the doorframe, hoping the trim wouldn’t come off in my hands. “Joshua, you agreed to give this time. I know it looks bad, but there’s nothing that can’t be repaired. Don’t forget what your therapist said when you told him you were moving to Vermont. He thought it might be a positive change for you to leave the city and be in a suburban neighborhood.”

After several teachers and guidance counselors had shared concerns about Joshua’s inability to assimilate, I had hired a professional to work with him. While most people might have thought living in a metropolis the size of New York City would offer many opportunities for my son to socialize, the therapist thought the opposite. She believed it was too easy to be anonymous there—too tempting to return to our apartment and wall off the outside world. It wasn’t easy for kids to get together to play. The therapist, unsolicited, had told me she thought I was a recluse, too, which could have influenced Joshua’s outlook and lifestyle. She hadn’t bought my excuse that as a single parent, adopting Joshua after my sister Michaela—his biological mother—had died, hadn’t left me much time for a social life. I supposed the therapist had been right to doubt me. Joshua had been old enough for years to trust with a sitter. I just preferred to stay home with him.

“I know what Grandfather and Grandmother would say about this place,” Joshua noted.

My son was aware that there had always been friction between me and my parents. They had been too busy with their wealthy contemporaries to spend time with me or my sister when we were growing up. When Michaela had become pregnant and hadn’t been in a relationship with the unidentified biological father, my parents made clear she’d receive no support from them if she kept the baby. After Joshua had arrived, she’d struggled and, somewhere along the line, we had learned she was using. When I had received a call from my father to inform me that Michaela had passed, he was emotionless, more concerned about what to do with his then-one-year-old grandson. I volunteered to adopt him, which was met with protests and disapproval from both my mother and father. Since they weren’t offering to raise him, and I refused to hand him over to strangers and pretend he had never been a part of our lives, I’d done what I thought was right. It was the best decision I had ever made. I loved Joshua more than anything or anyone.

“You think your grandfather and grandmother would hate it?” I asked. Joshua nodded. “Well, then that’s one thing in this place’s favor.”

Joshua laughed for the first time since we had left the city apartment. “That and living farther away from them means I won’t have to visit them as often.”

I squeezed his shoulder. “I know you don’t enjoy your time there. Joshua, I don’t agree with all their views either, or how Grandfather pressures you to one day be a part of his cigar-smoking, golf-playing clique and secure a job on Wall Street. He used to do that to me, but I still did what I wanted and became a writer, and you’re free to choose your career, too. I trust you to absorb from them what’s helpful and ignore what isn’t. And I hope that they’ll include you in their will one day since you’ve always been respectful and good to them. But yes, I suppose we do have a legitimate excuse for you to visit less frequently.”

“What are you going to do about fixing up this place?” Joshua asked.

I shrugged. “Guess one of the first orders of business will be finding a contractor. I’m not that handy.”

Joshua had a teasing grin. “Really? Good to know, Dad.”

I chuckled. He was only too aware. “Wise guy.”

Joshua surveyed the entryway with disappointment. “If we don’t like it here, can we consider moving somewhere else? It doesn’t have to be back to New York.”

“Sure, Joshua. We’ll give it a few months and see how it goes.”